by Susan Baron

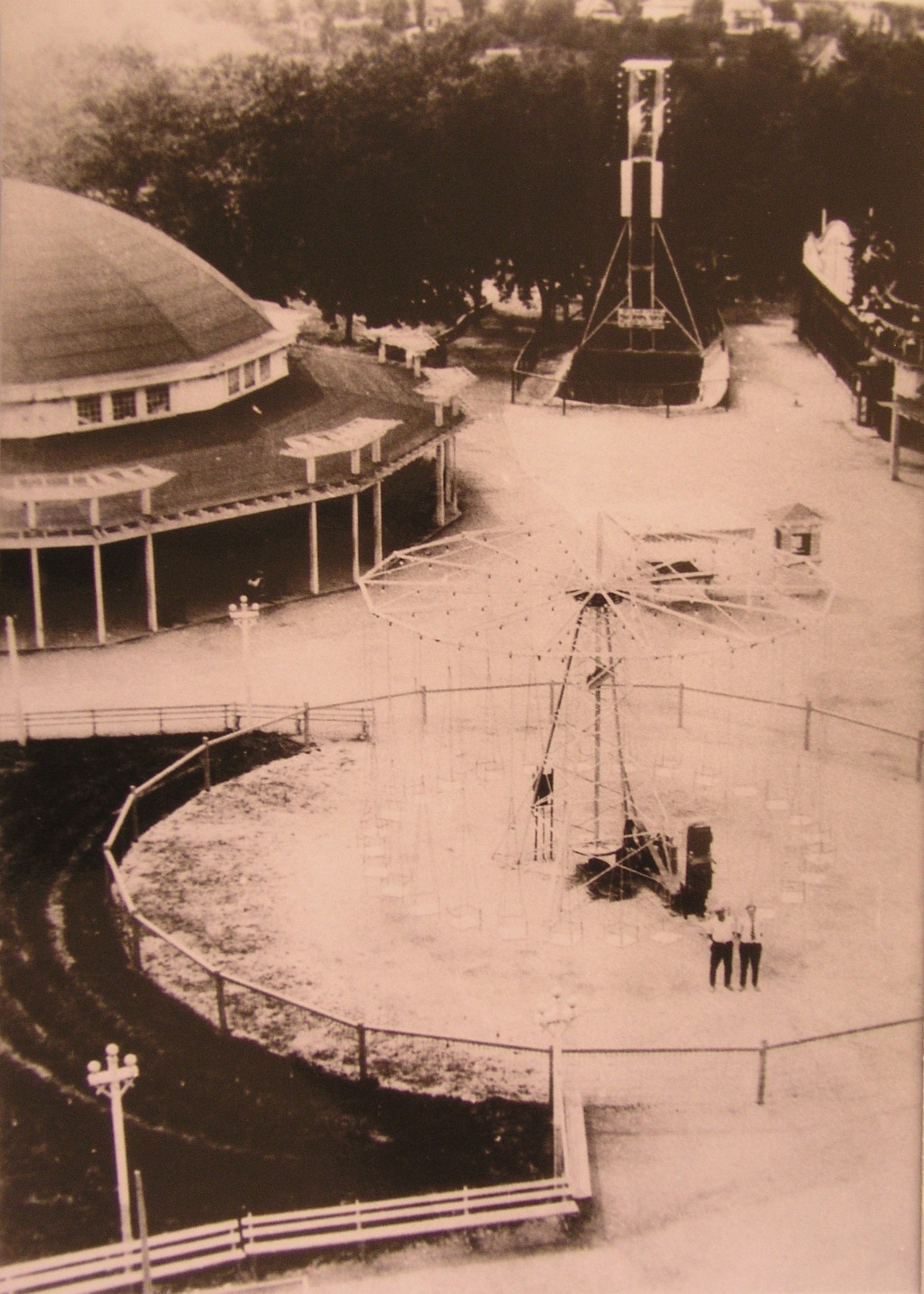

Mormon Pioneer Memorial Bridge, Omaha, Nebraska on Sunday, May 31, and Monday, June 1, 1953.

Source: Florence Historical Foundation, Bank of Florence Archives

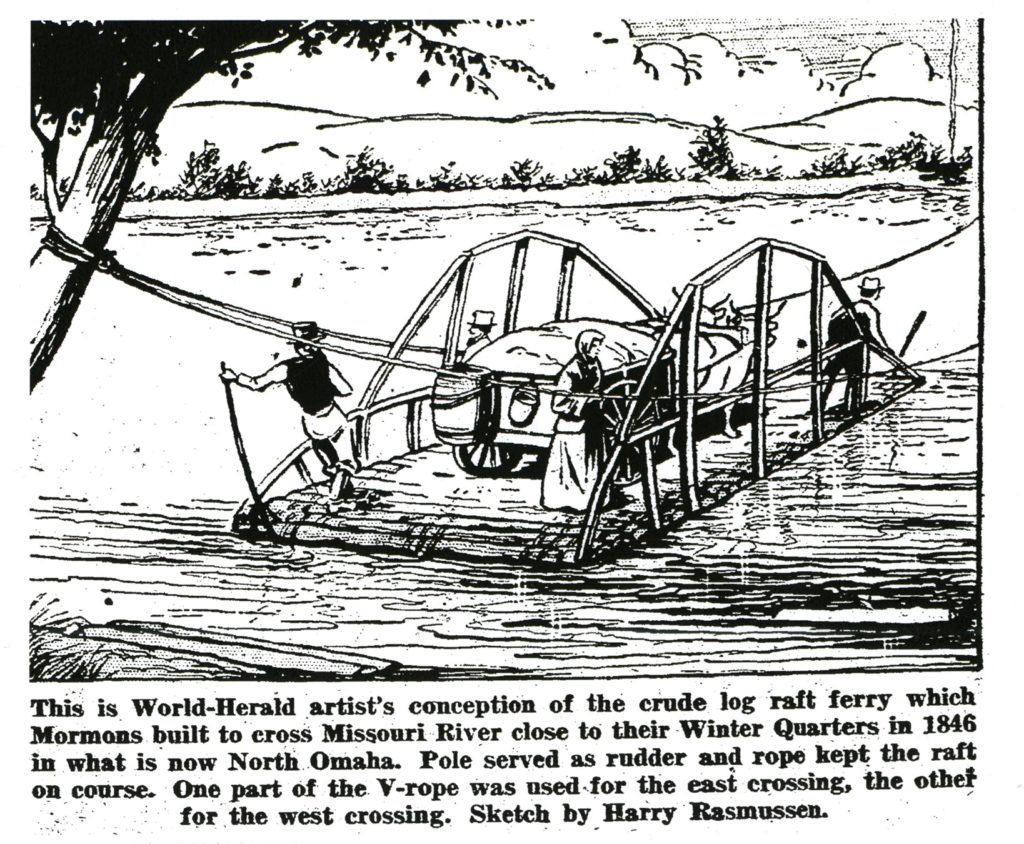

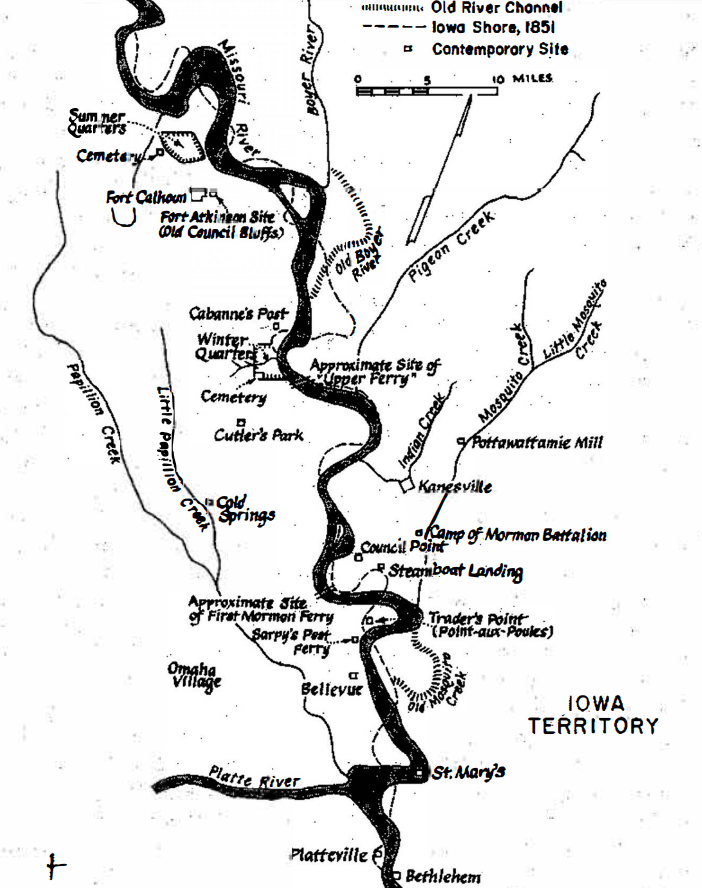

The ease with which we cross from Iowa to Nebraska on the Mormon Bridge is rarely given much thought, because it’s so easy. But getting across the Missouri River wasn’t always like that. In 1846 thousands of Mormons gathered on the eastern banks of the Missouri River, shielded their eyes from the setting sun, and wondered how they would ever get hundreds of wagons and thousands of people and heads of livestock across those muddy swirling waters to their Zion in the West. They couldn’t afford the steamboats that occasionally arrived from downriver to act as ferries. Always the problem solvers, Mormon men went to work and in two weeks constructed a rough ferry of logs. This ferry was located just north of where Peter Sarpy operated a small dingy at Bellevue and was the first ferry to operate regularly.

From the first of July 1846 until the fall of that year, wagons, families, livestock, and supplies were ferried from the Iowa side to what was then Indian Territory. By mid-September 1846, the site of Winter Quarters (modern-day Florence, NE) was officially selected. The Mormons moved their ferry north to Winter Quarters and located the landing probably at the mouth of the now-buried Mill Creek. In 1846 Mill Creek emptied into the Missouri River and there was a limestone footing at its mouth; one of the few places in the Missouri that such a footing was to be found so close to the surface. Wide, flat-bottoms or beaches on both the Iowa and Nebraska sides made this a desirable place for a ferry. And others would find it a good place to put a bridge.

(University of Oklahoma Press 1987) p. 48

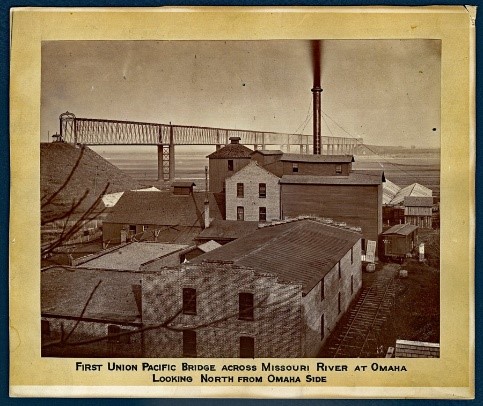

In 1854 James C. Mitchell founded the town of Florence, Nebraska literally out of the ashes of the 1846-47 Mormon Winter Quarters and was granted permission to incorporate the Florence Bridge Company by the U.S. Congress the following year. Mitchell had hoped that the Union Pacific railroad would cross there, and in that hope, he raised $200,000 to build a wooden bridge. The project only got as far as moving some dirt around on the Nebraska side before the financial panic of 1857 put an end to the endeavor. All hopes were dashed for a railroad bridge at Florence in 1873 when the Union Pacific constructed their single-track bridge. This bridge, however, did not serve wagons or foot traffic.

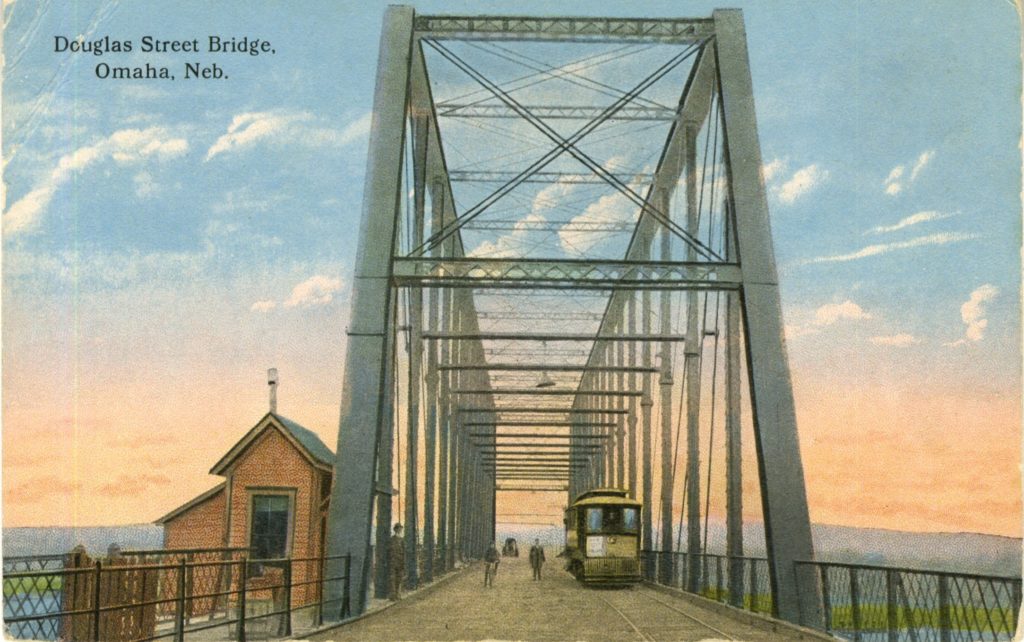

Omahans were sick of seasonal ferries, pontoon bridges, and crossing precariously on ice when the river froze. In 1888, the Douglas Street Bridge for streetcars with a walkway for foot traffic was completed. When automobiles became the preferred transportation, a twin sister bridge was added and re-named the Lincoln Highway Bridge, and eventually the Ak-Sar-Ben Bridge.

The Chicago, St. Paul, Minneapolis, and Omaha Railway managed to dig footings for a bridge at Florence in 1885 but went no further. 1891, 1905, 1914, 1922, 1926 and 1936 Florence talked about a bridge north of their city, but there was little action. By 1934, a second bridge in Omaha, the South Omaha Bridge, spanned the Missouri. The South Omaha Bridge delighted everyone: farmers, travelers, and particularly occupants of downtown Omaha. Before that bridge was opened, trucks odoriferous with manure would cross the Douglas Street Bridge from Iowa and drive through downtown Omaha to reach the packing house district. Whew!

By now, Florence was feeling very much left out. The only way to get to Florence from Iowa was to cross one of the two Omaha bridges and weave north through city streets. Time consuming and inconvenient.

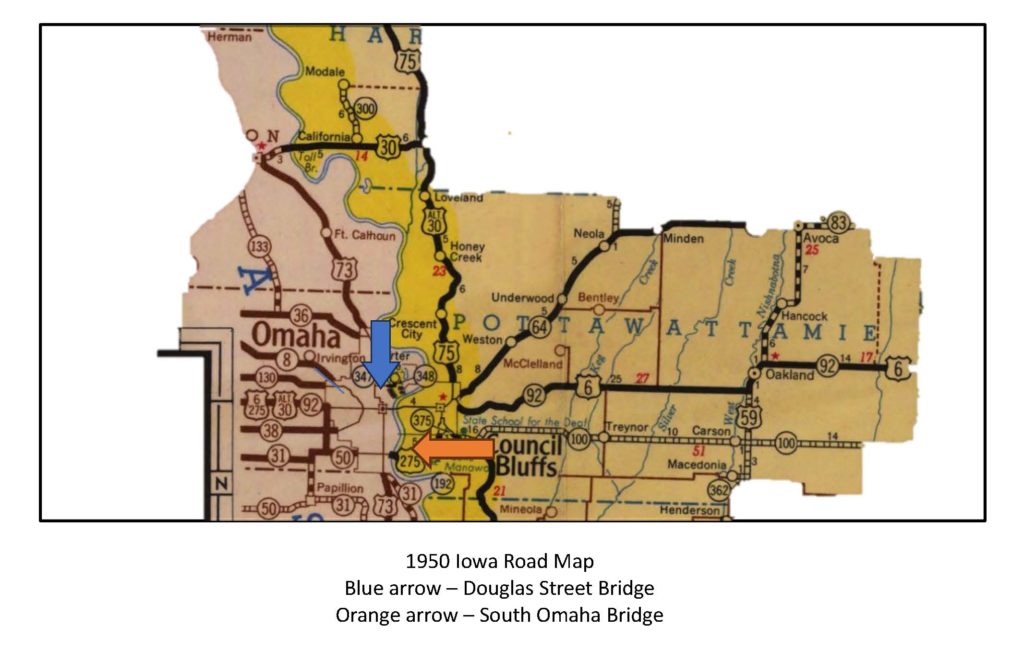

Back in 1950 getting around in a car was a lot more challenging than it is now, for there were no interstates. Highways were two-lane affairs which made passing difficult if not dangerous. The 1950 road map shows only two-lane options. The blue arrow points to the Douglas Street Bridge, and the route east across Iowa was on Highway 6 through every little town. Scenic, but slow. A traveler could also go north on Nebraska Highway 73, cross the toll bridge at Blair and connect to Highway 30. Again scenic, but slow. The orange arrow points to the South Omaha Bridge which seemed the best route to take going south to Kansas City.

Before the 1946 General Bridge Act, permission to build a bridge over an interstate stream required a franchise from Congress. The Bridge Act bypassed Congress and streamlined the process. In 1947 the Nebraska Legislation gave municipalities and county boards the authority to create and appoint bridge commissions. The time for a bridge at Florence was way overdue, but the North Omaha Bridge Commission was the public body to get the job done.

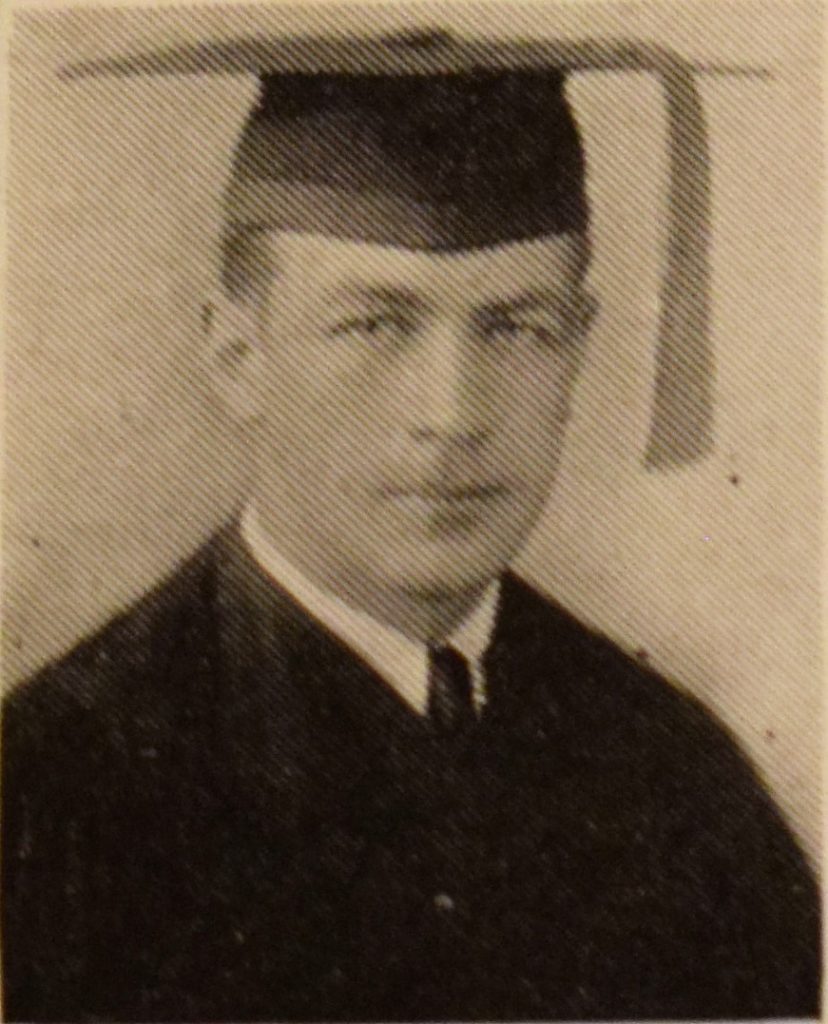

It was a protracted and often frustrating labor of love for The North Omaha Bridge Commission: Dr. H. L. Karrer, a retired dentist; manager L. Dale Mathews, banker; contractor and chairman William F. Schollman; and Marvin G. Schmid, attorney. These men were called “Heros of Mormon Bridge” by H. W Becker, and they truly were. The way Dr. Karrer put it, “This commission had neither money nor experience. All it had was the burning desire to succeed where others in the past had failed.”

Yet the commission dove into the job of getting the 1912-foot-long bridge built. They dealt with consulting engineers, contractors, material shortages, and even traffic engineers to confirm the bridge could support itself and pay off the bonds. Smith, Barney, and Company of New York were chosen to handle the issuance of $3,450,000 million in bonds (the cost to construct the bridge, the approaches to the bridge, and a bridge over Pigeon Creek in Iowa). With engineering plans and specifications completed on December 19, 1950, the contract for the bridge was let.

The road to build the Mormon Bridge was not always straight. Among several challenges was a lawsuit alleging the commission did not have the authority to sell bonds or build the bridge. The suit was dismissed but not without causing some anxiety. There were more obstacles.

Critical materials became scarce due to the ongoing Korean War and steel being allocated. Steel mills could only promise 2,000 tons of the 3800 tons needed for bridge construction, which left a shortfall of 1800 tons. Attorney Schmid and Dr. Karrer went to Washington and wheedled another 102 tons from the Federal government. Then another hero entered the picture. The State of Nebraska – standing tall – promised the needed material out of the state’s steel allowance.

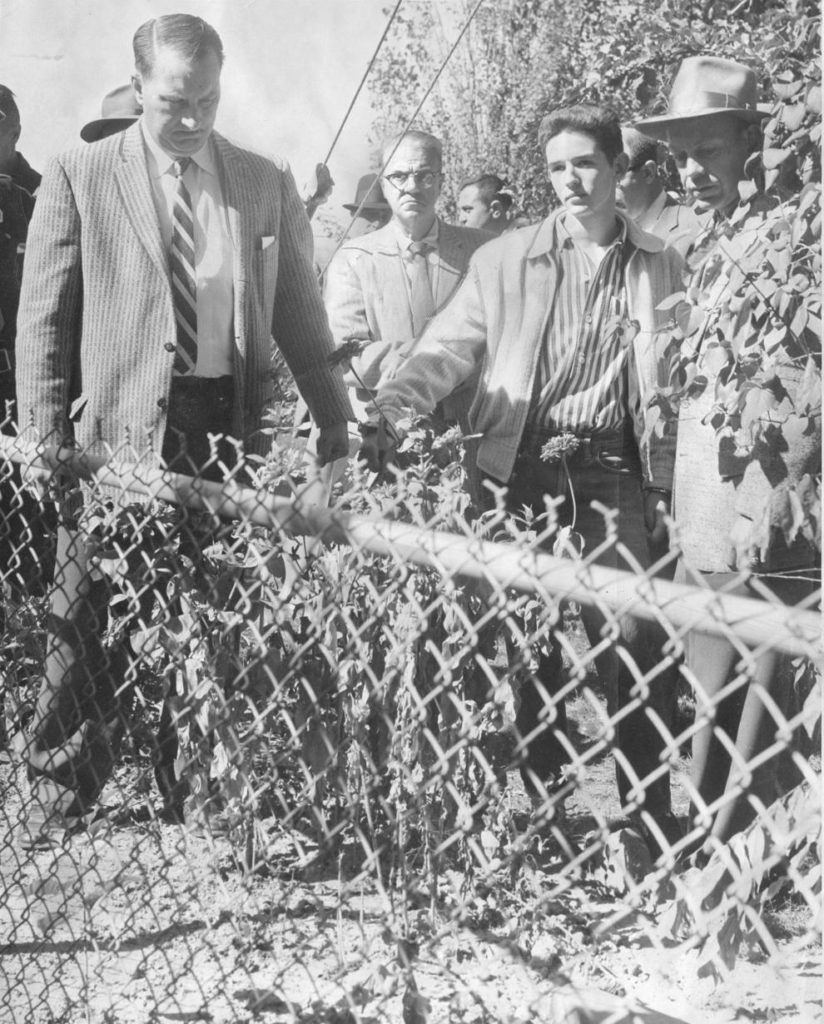

By April 1951, equipment moved in to drive piles, move earth, and secure the steel girders for the roadbed. The official groundbreaking ceremony took place on May 12, 1951, with about 500 dignitaries in attendance. Dr. Karrer said, “The commission and the people of Omaha feel that we have been greatly honored by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints in giving approval to name the structure the Mormon Pioneer Memorial Bridge, and one of our greatest desires is to have the Church and its official representatives take a leading part at the dedication ceremonies.”

By the summer of 1952 just 4,000 feet of the Iowa approach needed to be laid. The toll plaza was nearly completed, and truss work had begun.

Everything was on schedule for an October or November 1952 opening, and then came the infamous April flood of 1952. Fortunately, the area around the bridge was not greatly affected by the flood waters, and the official opening of the Mormon Bridge was only delayed until December.

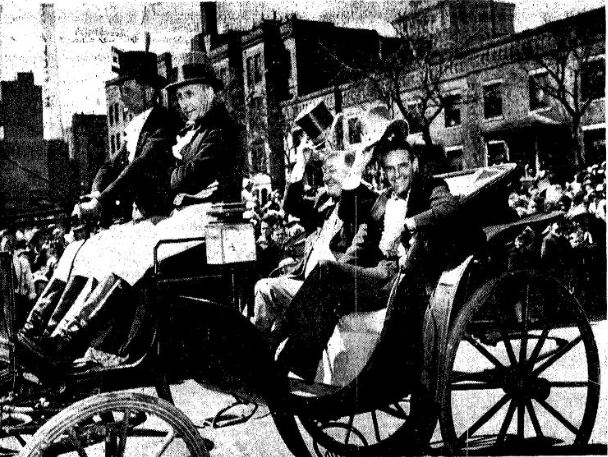

The official opening on December 14, 1952 was a modest affair compared to what the dedication would be the following year. A few speeches, a ribbon cutting, and then cars and trucks streamed across. Dr. Karrer said 4,000 vehicles passed over the bridge the Sunday after it was opened. One old-timer, Harold Bergquist, present at the opening, told of crossing the Douglas Street bridge in a horse and buggy as a boy of five.

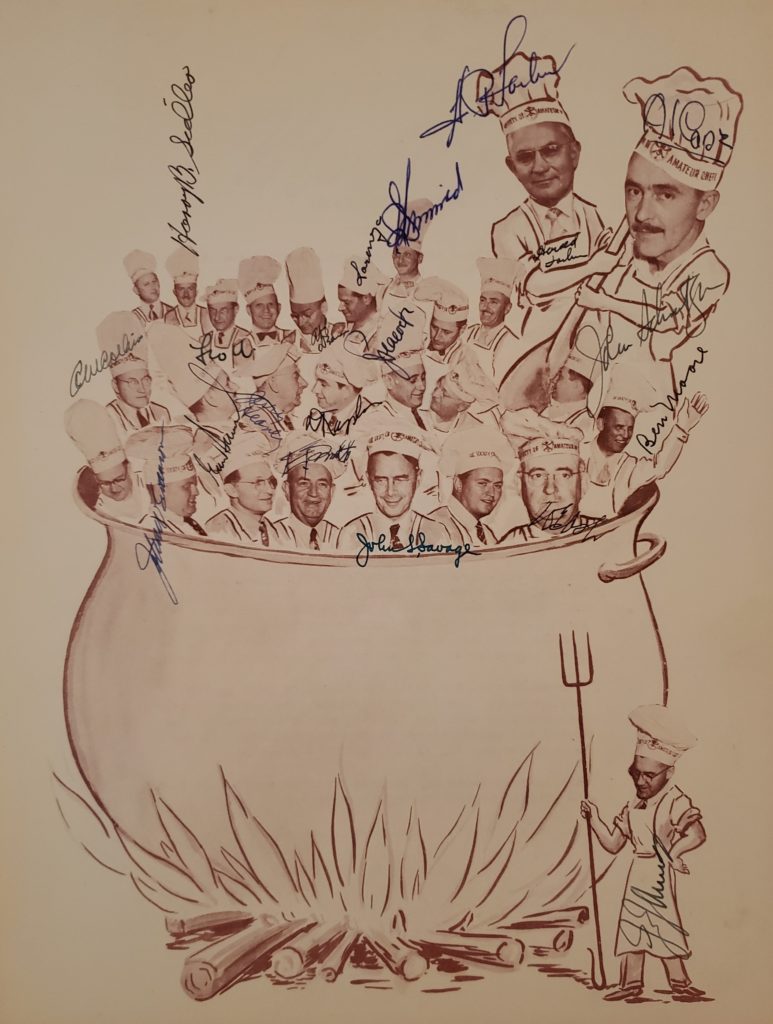

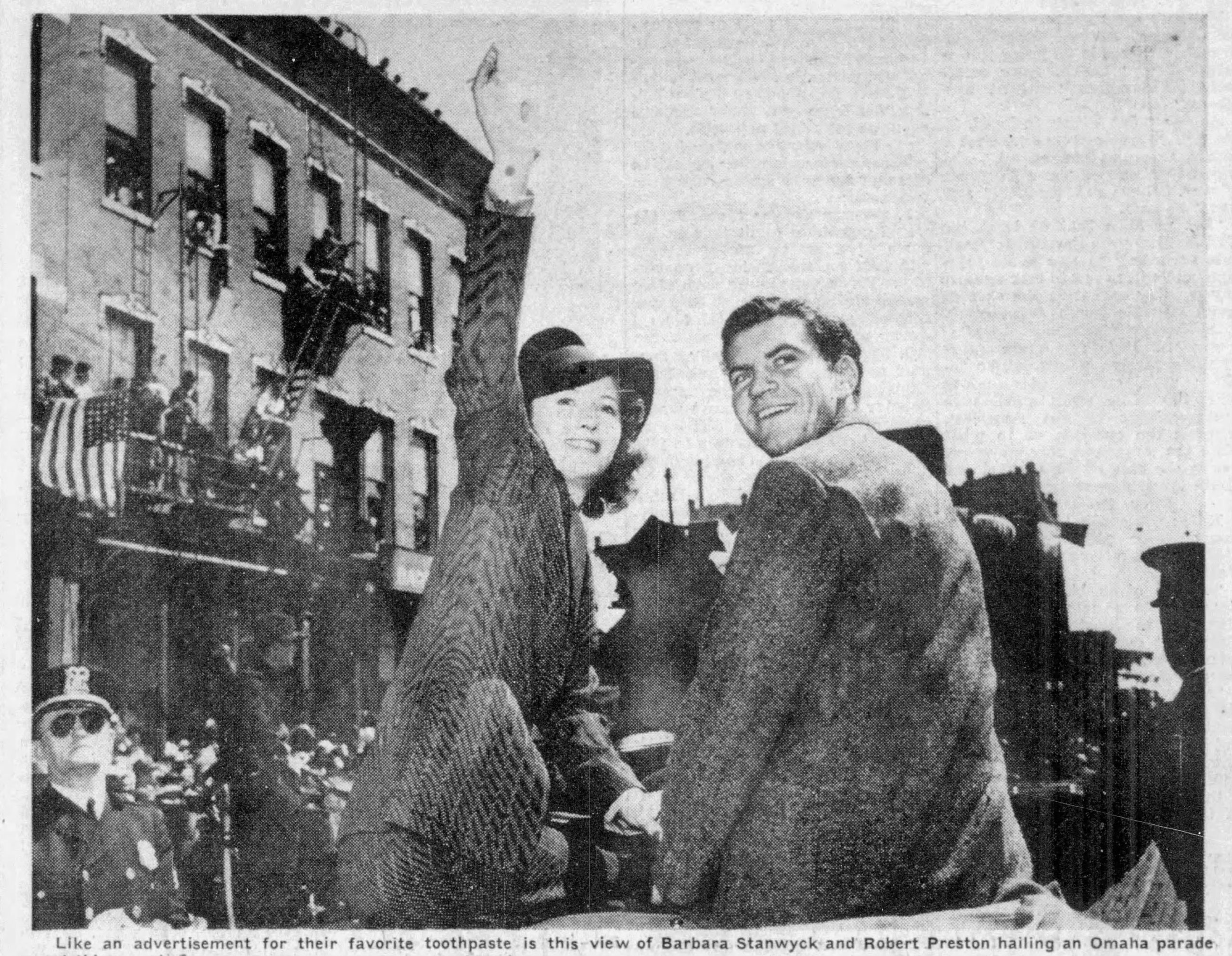

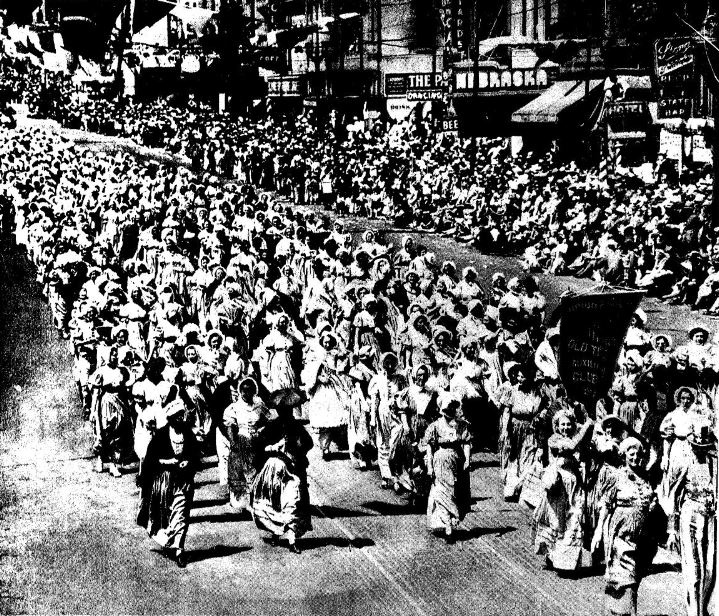

Kick off for the elaborate dedication ceremonies of the Mormon Pioneer Memorial bridge began with the meeting of five civic clubs from North Omaha and Florence. Twenty sub-committees were formed, and police, highway patrol, and sheriffs from Council Bluffs and Omaha were engaged to handle the expected crowd of 25,000. The days’ events would include a religious ceremony and a huge parade.

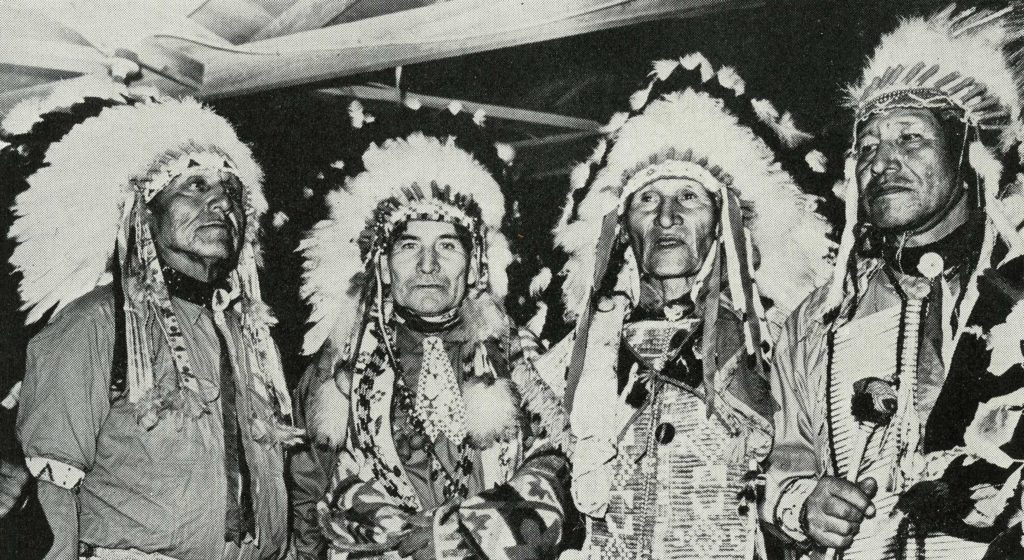

The sunrise in Omaha on May 31, 1953 was 4:53 a.m. The day was going to be hot and humid with no precipitation and little wind. The Missouri River was at 5.0 feet, down from its norm of 9.3 feet. At approximately 8:00 a.m. a special 18-car Union Pacific train pulled into Union Station with leaders and members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, including President David O. McKay, on board. In addition, 45 Palomino horses from the Weber County Utah Sheriffs Mounted Posse traveled in three cars attached to the train. More Mormons arrived by motorcade. Descendants of Brigham Young and church founder Joseph Smith were present as well to add luster and significance to the two-day program. The North Omaha booster called it the largest gathering of Mormons in Mormon Church history.

Dignitaries were feted at a noon luncheon followed by a program at the Mormon Pioneer Cemetery with speeches by members of the North Omaha Bridge Commission and leading representatives of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. That evening “an epic cantata” was performed by 100 voices from Brigham Young University at Ak-Sar-Ben coliseum. The cantata depicted the 1846 Mormon trek across Iowa.

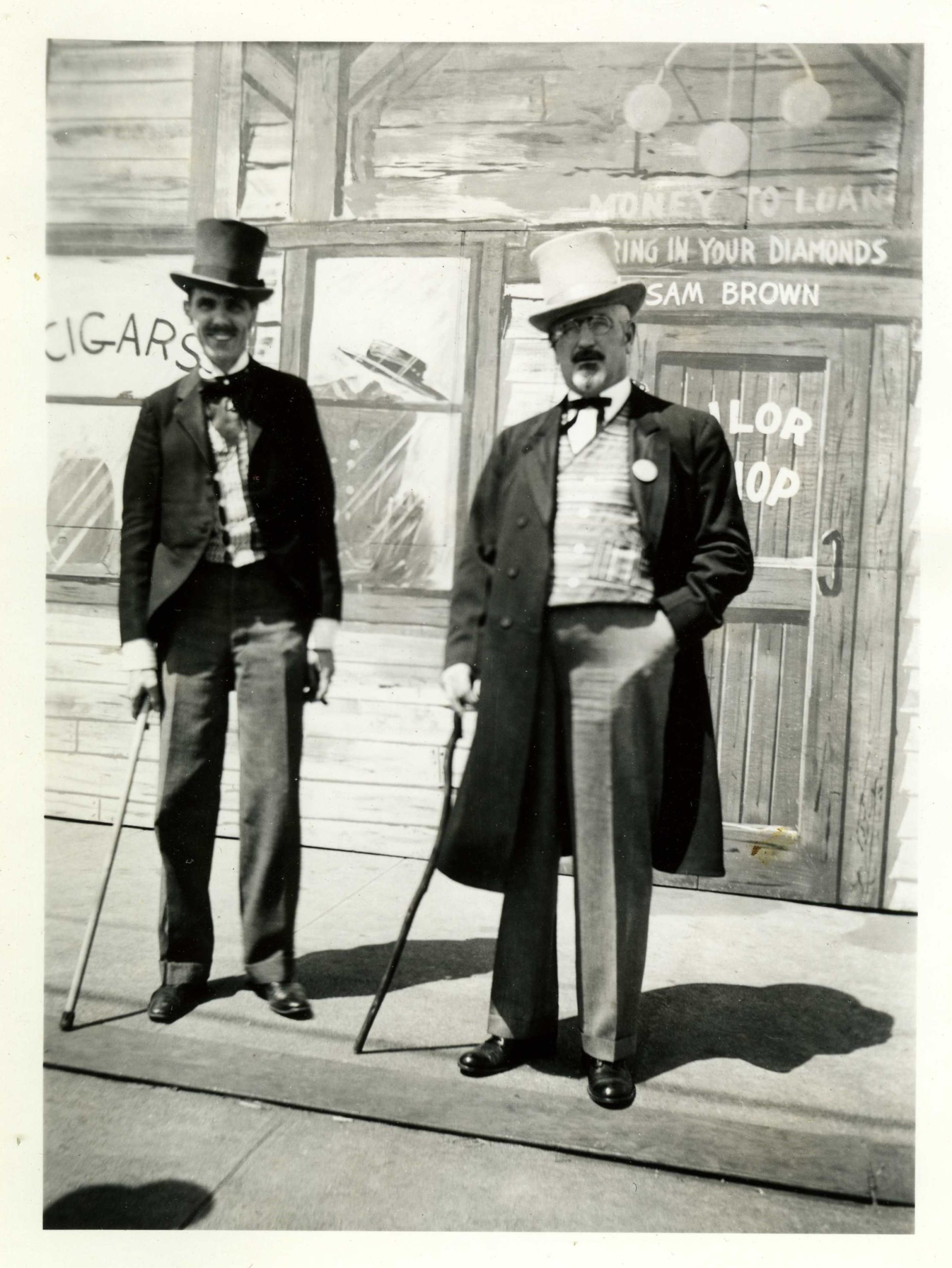

The next day, June 1, (coincidentally Brigham Young’s birthday) was just as packed with activity and symbolism. At 9:00 a.m., a long line of cars carrying mayors, governors, church leaders, members of the North Omaha Bridge Commission, army officials, and politicians crossed the Douglas Street Bridge in downtown Omaha to Council Bluffs. The 20-car motorcade then circled north to Cresent, Iowa and as a symbol of the Mormon pioneers crossing in 1846, drove across the Missouri River on the Mormon Pioneer Memorial Bridge into Nebraska. The motorcade then joined the main parade beginning at 30th and Ames.

Florence businesses gave prizes for the best window displays showing materials used by the Mormons during their stay at the Winter Quarters. Items included an 1845 coverlet made from flax that was grown, spun, and woven on a farm near Nauvoo, Illinois, a chest and blankets from a covered wagon, a washboard, two brass buckets made in 1849, a saddle maker’s bench, and kitchen and eating utensils of the period.

By 1969 the Mormon bridge was financially sound, but it would be another ten years before the bonds would be paid off and the bridge made toll-free.

A sister span was added in 1978 before the bond was paid off which disgruntled some bridge crossers. Bridge traffic going into Iowa had to pay a toll, but traffic coming into Nebraska paid no toll.

Source: From the Omaha World-Herald Photography Collection at Durham Museum

That situation didn’t last long. April 21, 1979, the last toll was collected. The $3.45 million bond was paid off two years earlier than projected and left $40-$50 thousand to spare for future bridge maintenance. Crossing the bridge was now toll-free both ways. The toll booth, scheduled to be moved in late June 1979, was delayed until early July due to rain. It now resides in Florence behind the old bank and is occupied by barber, Dick Brown.

The bridge has not been neglected. In 2018, the original bridge underwent an $11 million refurbishment that involved lead paint remediation, repairs to the bridge deck, and a new asphalt driving surface. Cars, trucks, RVs, and even electric vehicles easily cross where once there was only a ferry.

What would the pioneers of 1846 say if they could see the Twin Bridges now? I imagine they would be thankful there was no need for a ferry, and then, without hesitation, urge their teams onto the roadbed of the Mormon Pioneer Memorial Bridge continuing West to their chosen Zion.

Sources:

North Omaha Booster

December 19, 1952 #51

Friday, May 8, 1953 Vol 29 #19

Friday September 11, 1953

Friday May 29, 2953

H. W. Becker “Heros of Bridge”

Sunday Omaha World Herald

May 17, 1953 pg. 99

May 24, 1953 pg. 17

May 31, 1953 pg. 17

Evening Omaha World Herald

May 26, 1953 pg. 1

May 27, 1953 pg. 1

May 28, 1953 pg. 5

July 4, 1979, picture

Karrer, H. L. ERA Improvement April 1952 228-229 “The Mormon Pioneer Memorial Bridge”

Fletcher, Adam “A History of the Mormon Bridge in North Omaha”