By Bob Lohman

This week we honor the sacrifices of our nation’s military veterans on Veterans Day, a holiday that began as Armistice Day, commemorating the silencing of the guns in France at “the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month.” With the holiday’s roots in World War I, it is an appropriate time to remember Fort Omaha’s contributions during the Great War—namely the operation of the Army’s Balloon School. It is hard to read the words “balloon school” without smiling over such an anachronistic sounding institution, but balloons were no joke in the early era of aviation. They provided a stable platform for observing enemy movements and time aloft was not constrained by fuel capacity. While the era of manned observation balloons largely ended on Armistice Day 1918, Fort Omaha’s balloon soldiers made their mark on the battlefields of the western front and contributed to the defeat of the Kaiser’s army.

Fort Omaha actually hosted two Balloon Schools; the first from 1908-1913 and the second, which encompassed World War I, from 1916-1919. Balloons saw their first use by the U.S. Army in the Civil War. While not a huge success, the ability to observe enemy movements from above remained alluring and military balloons were again employed during the Spanish American War with mixed results. In the early 20th Century U.S. Army, the operation of balloons and aircraft was the responsibility of the Signal Corps. Originally, the Signal Corps planned to house the balloon effort at Fort Myer, Virginia; however, they were unable to construct a hydrogen plant there and transferred the balloon school to Fort Omaha, the home of the Signal Corps’ school for non-commissioned officers.

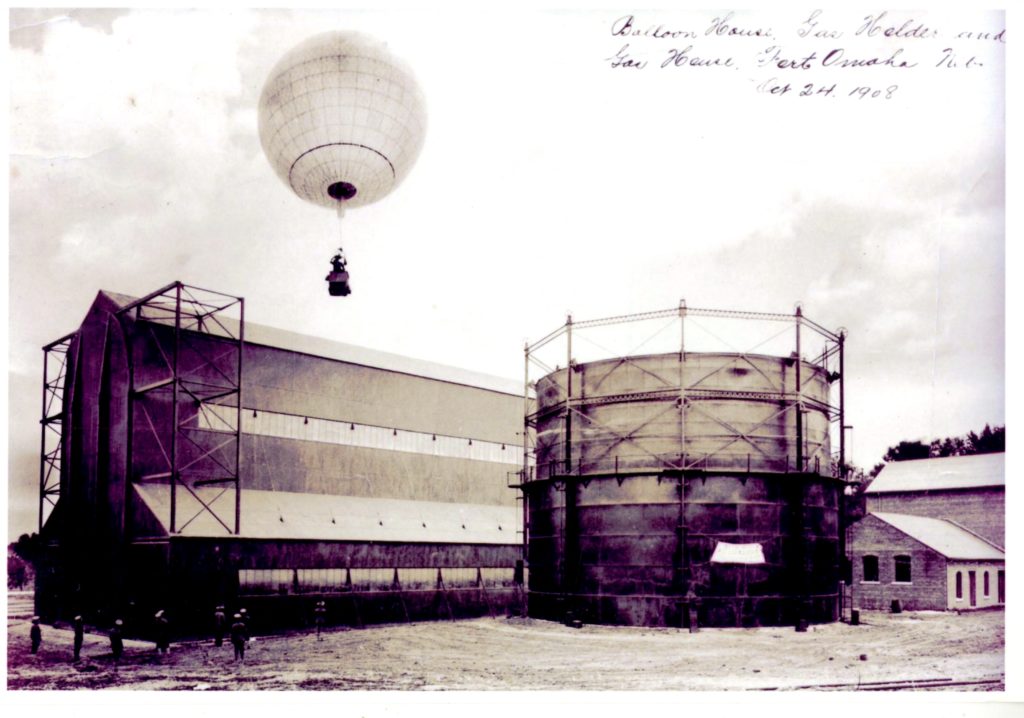

Construction of a balloon hangar and hydrogen plant began in 1908 and the first balloon filled with hydrogen generated at Fort Omaha ascended in April 1909. The school conducted classes for balloon pilots every May until it closed in October 1913, when the cash-strapped Army decided to concentrate its limited aviation funds on airplane development. Less than a year later, World War I broke out with the assassination of Austrian Archduke Ferdinand in Sarajevo. While the United States managed to remain neutral through the first three years of the conflict, by 1916 the Wilson administration deemed it prudent to develop more robust military capabilities to protect American interests. A growth in aviation was part of the Army expansion, and since observation balloons were widely used by both sides in Europe for directing artillery, the Army decided to re-establish its Balloon section. Fort Omaha, which had retained its hydrogen generation plant and balloon hangar, was the logical site for the new operation, and the reborn balloon school was opened there in November 1916. Five months later, the United States entered World War I.

The balloon school at Fort Omaha conducted two types of instruction. The first course of instruction was for the “Flying Cadets,” volunteers learning to become balloon pilot/observers. Volunteers for the flying cadets included both civilians and junior enlisted men. Instruction was conducted in the former Department of the Platte Headquarters Building, commonly referred to as the “Old North Barracks” during the WWI era. The training was developed by Major Hersey (soon to be Commander of the balloon school) and encompassed topics like map reading, artillery observation, winch operations, telephones, panoramic drawing, cordage (knot tying), military skills, and meteorology. The students also benefited from the experience of the British and French advisors attached to the school. The cadets were housed in single-story buildings behind the “South Barracks” (currently called the Double Barracks).

The growing need for balloon pilots quickly outgrew Fort Omaha’s limited capacity and the Army contracted with a private balloon school in St. Louis to provide the aerial portion of the pilot training. That school moved to Camp John Wise near San Antonio, Texas in the fall of 1917. Flying cadets subsequently conducted their 3–4-month ground school at Fort Omaha and then spent a month at Camp Wise to complete the required 8 flights to receive their balloon pilot license. Upon successful completion of their training, the cadets were commissioned as Army officers and provided the leadership for the newly forming balloon companies.

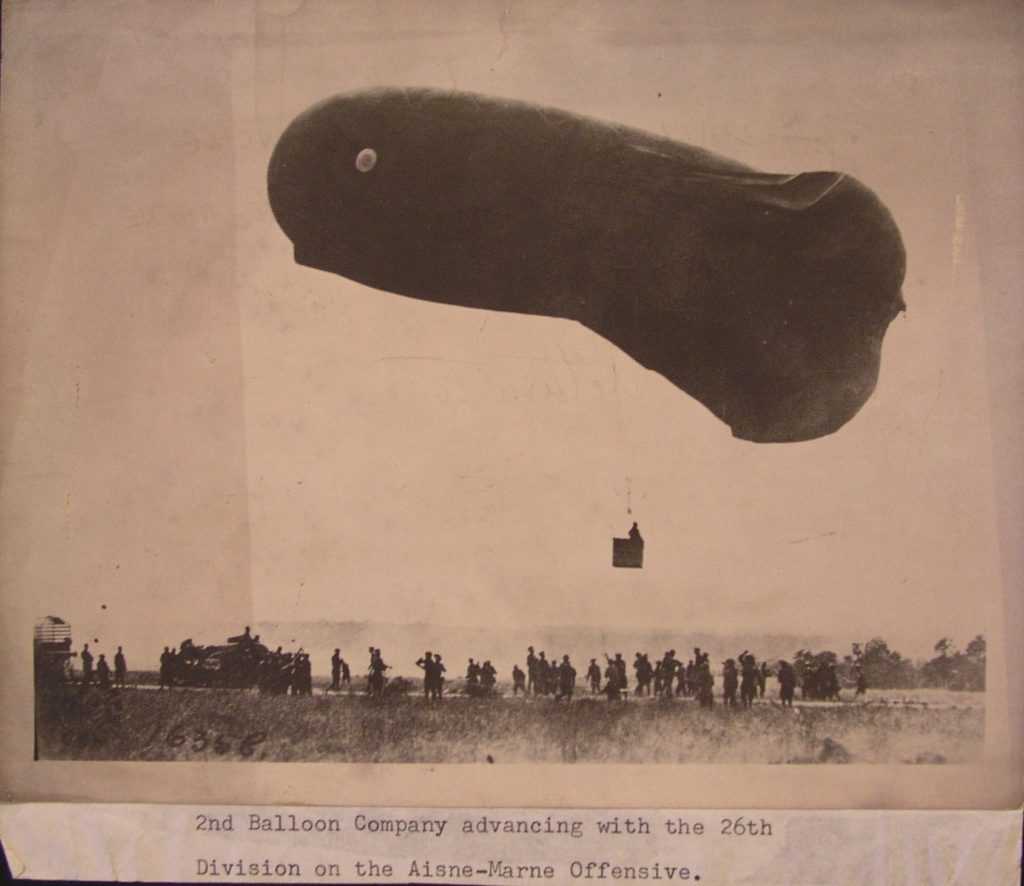

The second type of instruction at Fort Omaha was for the newly-formed balloon companies and the scores of enlisted men that performed the various support functions involved in assembling, launching, recovering, maintaining, protecting, and transporting the balloons. The designation, size and structure of balloon units evolved over the first year of the war, but by June of 1918 the Army had settled on numbered balloon companies consisting of 7 officers and 180 enlisted men that included observers, hydrogen specialists, a maneuvering detail, parachute packers, a basket detail, truck drivers, maintenance sections for the balloons and trucks, cooks, machine gunners, communications specialists, and an administration section. Each company supported one Cagout style balloon, a finned cylinder that looked like a smaller version of today’s blimps.

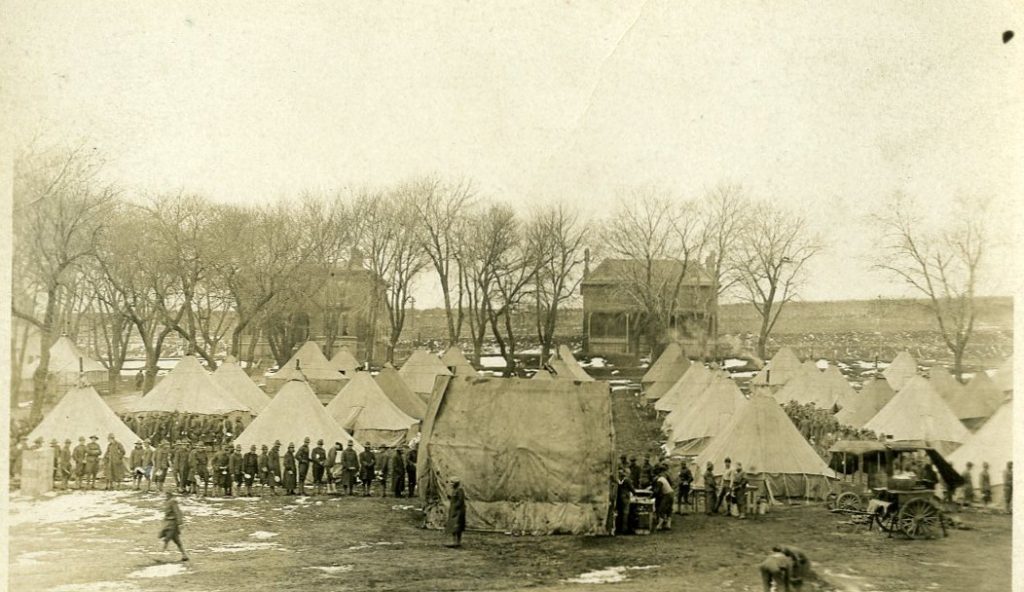

Draftees arrived at Fort Omaha from various locations and were assigned to newly organized balloon companies. After a period of basic training in “the school of the soldier,” the troops were taught skills like knot tying, filling the balloon, attaching the basket, operating the winch to raise and lower the balloon, and parachute packing. Soldiers chosen to be specialists like truck drivers and machine gunners were sent to courses at other locations and returned to their units upon completion of their training. Classroom instruction was conducted in the South Barracks building, but much of the training was of the “hands on” variety and performed on the parade field. One veteran recalled that the initial instructors were “tough old Army sergeants” who showed no mercy to the green draftees. Later, the cadre were drawn from balloon companies that had recently completed their training. The troops were predominantly housed in tent camps set up in the northwest part of the fort.

Note the General Crook House and Archive Center in the background.

The limited size of Fort Omaha and its tree-lined parade field meant no more than three balloons could ascend at one time. This severely constrained the school’s ability to meet the growing demand for new balloon companies to support the rapidly expanding American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), and the need for additional training sites became paramount. In July 1917, Company B was sent to Fort Sill, Oklahoma to serve as the cadre for a new balloon school at that location. In October, the Army leased 119 acres north of Fort Omaha and dubbed it Florence Field. The addition of Florence Field enabled the Balloon School to more than triple the number of companies that could be trained at one time. However, even this increase was not enough to accommodate all the balloon companies in training. In the summer of 1918, three companies were sent from Fort Omaha to establish a school near Acadia, California (Ross Field) and a month later three more Fort Omaha companies opened a training site at Camp Morrison, Virginia. Fort Omaha further expanded its training operation to Fort Crook (today’s Offutt Air Force Base) a month before the Armistice, using the fort to conduct basic training for new draftees. In total, some 17,000 soldiers passed through the various balloon schools.

While the flying cadets and school cadre were housed in barracks at Fort Omaha, everyone else slept in 8-man pyramidal tents. New arrivals in the winter of 1917-1918 had to draw platforms, tents, and stoves and assemble their new homes before they could go to bed. The veterans of that period recall the freezing temperatures and sleeping in their clothes with everything else piled on top of their cots for warmth. Fortunately, the weather began to warm up in April. The quality of food in the balloon companies was dependent on the competence of the company cooks. One veteran recalled that his unit’s cooks only knew how to make “slumgullion,” a cheap stew mixed with macaroni. Other veterans were luckier, with one even declaring he “ate better than he did at home.” Soldiers looking for some variety in their diet could find home cooking at the Red Cross food stands outside the front gate, and the Junior League of Omaha hosted a canteen for officers in the southeast corner of the post. For amusement on post, the soldiers could write a letter, have a doughnut, or find reading material at the YMCA. There was also a post newspaper, The Gas Bag, that provided Fort Omaha and Army news. Troops seeking more active entertainment could catch a trolley outside the front gate on 30th Street and head into Omaha to catch a movie or show, drink a beer, attend a dance and flirt with girls, or visit an amusement park. Several veterans mentioned the support and friendliness of the people of Omaha, stating they frequently received invitations to dine in civilians’ homes.

Training for the balloon companies typically lasted about five-to-six months. Reveille for the trainees was at 0600, followed by breakfast, policing the parade field, and work details. Training and balloon ascensions started mid-morning and continued until dinner. Simulated explosions were employed to train observers on adjusting artillery. One training detail mentioned (and disliked) by many of the enlisted veterans was digging balloon beds, which were large shallow balloon-sized pits that could accommodate a partially deflated balloon when not in use. The bed was covered with a canvas hangar or camouflage and provided shelter for the aircraft. Numerous balloon beds were dug at both Fort Omaha and Florence Field. Training with the combustible hydrogen-filled balloons could be a dangerous endeavor. In May 1918, a balloon exploded in the 14th Balloon Company at Florence Field while being deflated inside its shelter. Two soldiers were killed and twenty injured in the blast that was believed to be sparked by static electricity.

Once a balloon company completed its training, it shipped out to an embarkation port for transport to England and France. A veteran of the 2nd Balloon Company recalled his unit’s departure was highlighted in the dramatic local newspaper headline; “Angels of Hell Go to France.” Upon their arrival in France, the balloon companies were sent to one of two training camps run by the AEF. There they received additional instruction before deploying to support one of the infantry divisions. The 2nd Balloon Company was the first American balloon unit to arrive at the front in February 1918, followed by the 1st Company in March. Of the 35 Balloon Companies that made it to France, 17 would see duty at the front and make 1642 ascensions. The units that did see action were used hard. The 2nd Company spent 251 continuous days at the front and the 1st Company served from March until the armistice without relief.

Balloon companies performed multiple duties in combat. Connected to artillery units by field telephones, they called for and adjusted shelling on enemy positions. They also collected information on German positions and troop movements, which they captured in drawings, photographs, and reports that were sent to higher headquarters. Although they were strongly protected by antiaircraft guns, German aircraft attacked AEF balloons 89 times; 35 balloons burned and 12 more were shot down. Because the observers used parachutes to bail out when attacked, only one observer, Lt. Cleo Ross, was killed during the war when his burning balloon touched his parachute and set it ablaze. Two more observers were captured when their winch line parted and prevailing winds took their balloon into enemy territory. The balloon companies’ positions were also subjected to shelling and gas attacks whenever they ascended, making them very unpopular with the nearby infantry units.

The role of manned balloons in modern warfare ended with the Armistice on November 11, 1918. Airplanes and eventually helicopters and drones would perform the airborne artillery spotting and intelligence-gathering roles in succeeding conflicts. Of the 89 U.S. Army Balloon Companies that were formed during WWI, at least 38 spent some period of their training at Fort Omaha and Florence Field. As noted, only 17 balloon companies saw action at the front, although some 30 more were en route when the war ended. Following the war, the Army’s balloon operations were consolidated at Scott Field, Illinois, and Fort Omaha’s balloon school closed in the fall of 1919; Florence Field was returned to the heirs of the original owner and eventually developed into housing. After the war, the old balloon soldiers refused to fade away and formed the National Association of American Balloon Corps Veterans in 1932, publishing a quarterly newsletter, Haul Down and Ease Off, for several years. The balloon veterans’ organization also made periodic pilgrimages to Omaha for reunions and visits to Fort Omaha up until the early 1980s.

Sources:

“Balloons Up” – Short Life of the Army Balloon Service. (2022, April 1). Retrieved from Meandering through the Prologue: https://meaderingthroughtheprologue.com/balloons-up-short-life-of-the-army-balloon-service/

Balloons and Dirigibles in WWI. (2023). Retrieved from The National WWI Museum and Memorial: https://www.theworldwar.org/learn/about-wwi/balloons-and-dirigibles-wwi

Beemer, A. (1981). Interview with 9 Balloon Corps Veterans. (D. Dustin, Interviewer)

Havens, K. (1981). Interview with 9 Balloon Corps Veterans. (D. Dustin, Interviewer)

Herbert, C. (1981). Interview with 9 Balloon Corps Veterans. (D. Dustin, Interviewer)

Lieutenant William Collins (1918). Pictorial History of Fort Omaha. Omaha: U.S. Army Balloon School.

Mauldin, F. (1981). Interview with 9 Balloon Corps Veterans. (D. Dustin, Interviewer)

Moore, S. T. (1963). “When Sausages Blazed in the Sky”. Air and Space Forces Magazine, 85-88.