by Rita Shelley

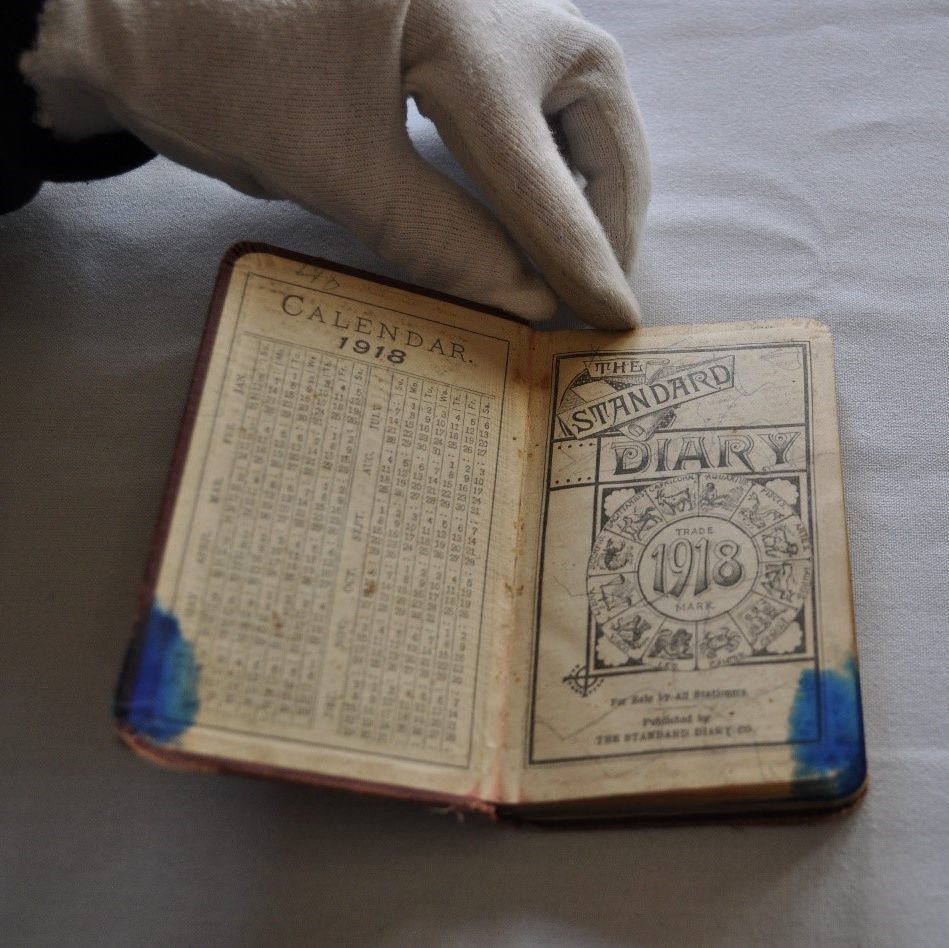

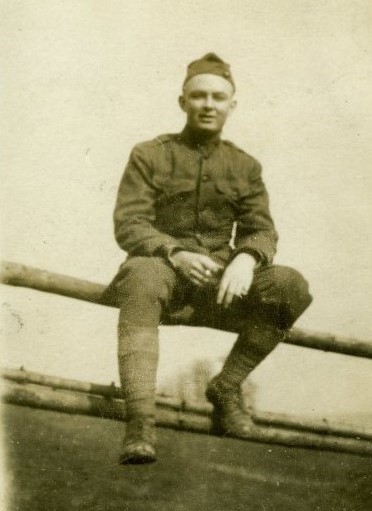

On December 6, 1917, Paul Borowiak, a 19-year-old from Omaha, enlisted in the U.S. Marines at Mare Island, California. Enlisting as a stenographer, Borowiak went on to serve with the Marines in decisive battles in France with the 18th Company, 2nd Battalion, 5th Regiment U.S. Marine Corps (4th Brigade, 2nd American Division). His wartime experiences are described in his palm-sized diary now in the Douglas County Historical Society’s archive. The diary covers May 2 to December 31, 1918. After the war, Borowiak also wrote a 14-page typed memoir specifically focused on the events of July 16-20, 1918. Historical accounts place the 2nd American Division on those four days at the Battle of Soissons on the Western Front, part of an offensive that culminated in an Allied victory. Its objective was to cut off a German supply route from Soissons to Chateau-Thierry in northeastern France. Historians contextualize the Germans’ loss as a turning point in the war.

In his memoir, Borowiak also reflected on the meaning of Soissons:

The purpose of this battle was to cut off the Soissons – Thierry road. If this could have been accomplished the entire salient would have been cut off with the resulting capture of thousands of Germans, plus guns. However, enough ground was taken by the 1st American Division, the fierce French Moroccan Division, and the 2nd American Division of which the Marines constituted the 4th Brigade, to put the Chateau-Thierry Soissons road under our artillery fire and made the German position untenable. A series of battles by other American Divisions gradually dislodged the Germans from the salient. It was practically the beginning of the end for the Germans. They never won another battle in World War I.

Early pages in Borowiak’s diary describe his first days in France. Two sentences recorded on June 9 couldn’t possibly have foretold what would be months of horrific combat:

Was playing baseball when the order came out that we would all move by morning to the front. Can consider this as really starting my war career.

On Tuesday, July 16, Borowiak’s company received orders to board French trucks at 10 p.m. Because of a shortage of trucks, quarters were cramped:

…worse than marching, particularly when it is taken into consideration that each Marine had a full pack on his back, full belt of ammunition, plus rifle, canteen, bayonet and helmet. The operation and the ride were about as bad as anyone could picture.

The following day brought ever more horrific scenes, including trenches half-filled with water, artillery shells detonating after striking trees, shrapnel “raining down from above,” and an assignment to be a runner for a captain who was killed later in the day.

The road was positively choked with traffic consisting of supply wagons, machine guns being drawn mostly by mules, caissons, etc. Occasionally you would slip in the mud and down you would go into the culvert. Then the next time you might slip in the other direction and – bango – right into the rear end of a mule, or it might be the wheel of a caisson, or any part of the side of a supply wagon or truck. Occasionally a lightning bolt would strike a tree and there would be a deafening roar of crackling shattered timber.

Thursday, July 18 brought casualties of two-thirds of Borowiak’s company, even though “thousands of prisoners and guns” were captured. There were “many, many dead and wounded laying on the field, some very pitiable sights.”

The next day, Borowiak became separated from his company. Upon rejoining, he observed that most of the company was missing, and learned that out of what had been a company of 250 men, he was one of only 18 still alive. He later reflected on the meaning of July 19 when Allied forces’ decisive win was still in the balance:

I have often wondered what the results of World War I would have been had those two columns of Germans that surrendered after we emerged from Cotterets Forest, and other columns of Germans that surrendered to the 1st American Division and the fierce French Moroccan Division, who were the other two divisions in this sector, had fought as the Germans did later in the day on July 18, 1918. In my opinion we would have positively won the war, but certainly not in the year of 1918.

According to the World War I Museum, Germans first used chlorine gas in 1915, using cylinders that they had embedded in the ground. The asphyxiating chemical warfare is said to have cost lives of three percent of its victims.[1] Still, hundreds of thousands suffered burns to lung tissue resulting in temporary and permanent injuries. According to Borowiak’s entry on July 30, 1918, his symptoms ran their course in about two weeks. He doesn’t say where or exactly when this exposure occurred, but describes its toll in a matter-of-fact tone:

During all these days was suffering from the effects of chlorine gas, although I took it to be a cold. …. I took off my gas mask because it was too difficult to breathe. It must have been here that I got a dose of gas. Luckily for me it was Chlorine gas and not Mustard gas. I did not report to sick bay because I was afraid they would transfer me to some other outfit and I did not want to leave the eighteenth company.

Borowiak was honorably discharged on August 13, 1919. In just two years’ service, he had risen to the rank of Sergeant Major. In his memoir, he summed up what he had survived:

The battle of Soissons added up to the almost unbelievable total of 92 hours of constant movement by French trucks, by foot, by being under terrific counter barrages and artillery fire, by being under machine gun fire, even by being strafed by a lone German aviator, by being the targets of snipers, and this without any hot food whatsoever and very little water, and practically no sleep at all.

Omaha city directories show that Borowiak settled into civilian life, first as a shipping clerk at a department store in 1920. By 1930 he was a detective for the Omaha Police Department. He and his wife Alice are listed in the 1940 Federal Census as the parents of two children, James and Gloria. By 1940, Borowiak owned a bar and ballpark. In 1964 he purchased Vinton Bowl, and served as president of the Omaha Bowling Proprietors Association. Upon his death on Nov. 17, 1970, that day’s Omaha World-Herald described him as having also operated Fallstaff Softball Park, the “headquarters of top-notch Omaha softball” in the 40s and as having been a member of the Omaha Bowling Hall of Fame. He had also been “a steadfast booster” of the World-Herald Good Fellows’ annual charity tournament.

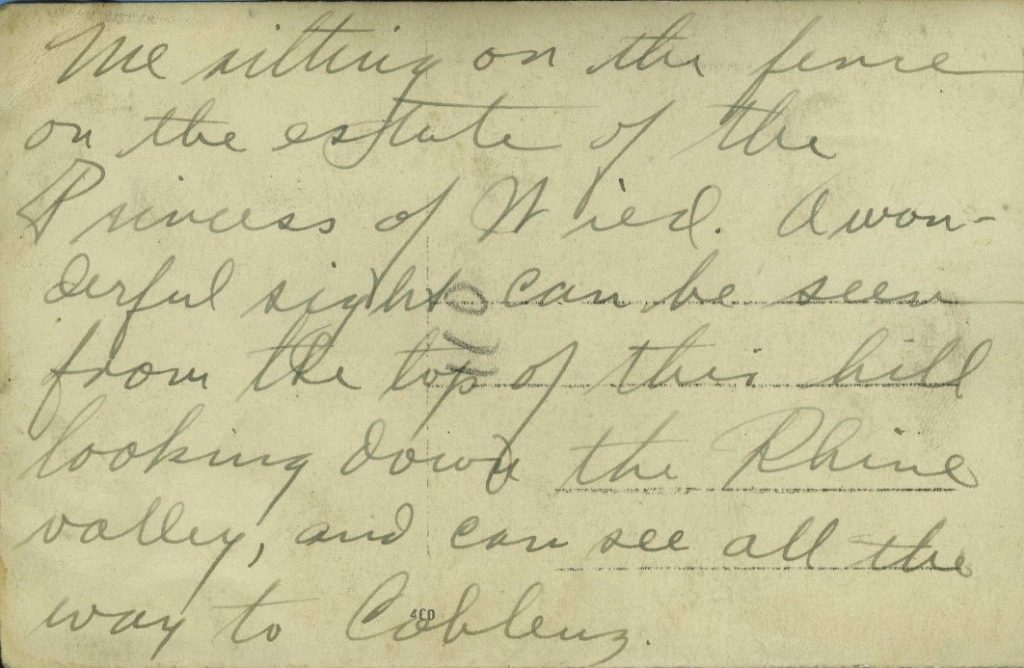

The Borowiak collection housed at DCHS includes not only Paul’s journal and memoir, but also several photographs, military documents, maps, field materials, and pieces of his uniform. It’s a remarkable physical record of an important period in modern history, but also allows researchers today to delve with extraordinary depth into how this period was lived and remembered by one young man from eastern Nebraska.

[1] “First Usage of Poison Gas.” National World War I Museum and Memorial. https://www.theworldwar.org/support/donate-object/recentacquisition/poison-gas